Welcome back to Reading the Weird, in which we get girl cooties all over weird fiction, cosmic horror, and Lovecraftiana—from its historical roots through its most recent branches.

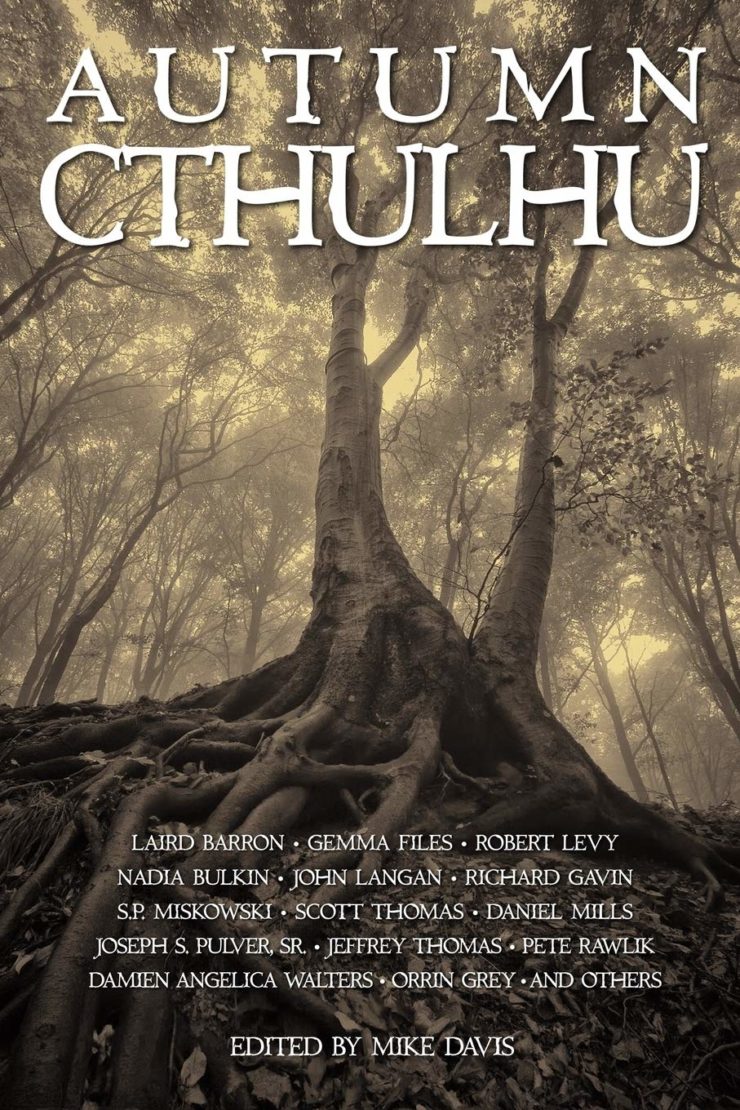

This week, we cover Wendy N. Wagner’s “The Black Azalea,” first published in the Mike Davis’s 2016 Autumn Cthulhu anthology. Spoilers ahead. Content warning for cancer and animal death.

“Perhaps waking up to apocalyptic sci-fi had put her in a dispirited mood, or perhaps it was the agent’s young face and stylish jacket.”

Candace Moore has recently lost Graham, her husband of thirty-eight years, to pancreatic cancer. She retired early to care for him through the six months of his illness. Now she lives in the cottage Graham lovingly rebuilt, alone except for her big orange tomcat Enoch, sleeping on the couch because her bed feels too large and cold.

Now the azalea he planted under the old elm tree is also dead. The tree succumbed to Dutch elm disease; the sunburned azalea, after one last sad burst of flowers this spring, it has withered to a dry gray skeleton. On what may be the last sunny day of autumn, Candace’s clippers make quick work of the brittle branches. When she hacks into the main trunk, however, a stink like old drains and fish assails her. The heart of the dead azalea is black, strangely juicy. To keep the blight from spreading, she digs out the roots as well. She leaves the jagged black hole to fill in the next day. She doesn’t want to fall into it, break a leg, lie helpless with no one but Enoch around. The world is “a vicious, ugly place for a woman alone.”

The following morning Enoch accompanies her outside. He growls at something Candace can’t hear or see. What she can see is that daisies near the azalea hole are drooping, lower leaves blackened. And the mildew-fish stink is worse. This evidence that the azalea blight is contagious across diverse species sends her inside to call the university extension office. The extension agent sends her out with a yardstick to estimate the extent of the problem. While measuring, Candace notices that grass and dandelions around the hole are also blackening. The leaves feel like they’re bleeding. Could this be some sort of plant Ebola? Can it spread to animals as well? Though the agent is “almost positive” she’s in no danger, he asks her to stay out of the garden until he can come take samples the next day.

Candace spends a restless night in front of the TV, waking (disconcertingly) to the end of Invasion of the Body Snatchers. Her neck is stiff, her mouth dry; later, there’s a little blood in the toothpaste she spits out. Maybe she’s brushed too hard while hurrying to greet the extension agent, Michael Gutierrez. She leads him into the garden, and notices the yardstick she left across the hole has now fallen inside it. The hole has widened; the stench is worse; the grass around it has collapsed into stringy black slime. Both notice the absence of insects, birds, the resident squirrels. Gutierrez collects samples, listens with concern to Candace’s idea that the unknown blight may be affecting underground plant material and causing ground subsistence. As he leaves, Enoch darts out of the house and over the fence.

Buy the Book

Star Eater

Candace envies the agent his excitement over a disease he may be first to write up. She was also once the “hot dog” of her office, and now she wonders if she shouldn’t have retired, whether Graham’s cancer has cut off her life, too. She recalls how his illness progressed exactly as predicted, every deadly milestone right on schedule. She calls Enoch, but hears only a distant high-pitched metallic clicking, perhaps from a passing train.

At 7:30 that night, her cell phone wakes her from a too-long nap. It’s Gutierrez, with test results that show no markers for a known plant disease! He’ll be back tomorrow with his whole team. Candace, stiff-hipped, creaks to the back door and calls Enoch again. A thin meow sounds from the azalea hole, which has grown to a pit big enough to swallow her whole. In the dark at its bottom she sees two iridescent red eyes.

She kneels, reaches toward Enoch. He mews piteously, but doesn’t leap out of the pit. That metallic clicking she heard earlier? It’s coming from the pit, louder now, as if closer and picking up speed. Threads of black flit over Enoch’s red eyes; panicking, Candace tries to lift him out of the pit. Immovably stuck, he screams and claws her arms. The clicking grows as alien as the stench accompanying it. Candace at last wrenches the shrieking cat free and runs toward the house. In the light from the door she sees that her arms and shirt are soaked with black goo and that Enoch has become “a black-soaked rag of a thing with no legs and no tail and raw red flesh from the shoulders down.” Whatever is killing the plants has gotten him. It’s new, all right, “something from a darkness beyond anyplace she knew, but had perhaps dreamed of. Something that was coming to swallow them all.”

Showering does nothing to wash off the stink. The clawed flesh on her arms is black and puckered. Her eyes are sunken in dark rings. Her mouth tastes of mildew. Later she will spit darkening blood as she waits for dawn to show her the pit. The pinging of “the thing’s imminent arrival” continues, hypnotic, urging Candace to crawl inside the pit.

Yes. She’ll go out there and “pull the darkness over her safe and snug.” When Gutierrez and his team arrive, she’ll show them “what the black azalea had reeled in with its roots and what was chugging along toward them all: right on schedule.”

What’s Cyclopean: Everything this week is hungry or mouthlike: Michael hungry for publications, “green toothy leaves,” the hole like a “broken-toothed mouth,” a breeze with teeth.

The Degenerate Dutch: Candace worries that Michael will assume an old woman is making things up, but manages to convince him to take her seriously.

Weirdbuilding: Echoes here of “The Color Out of Space,” and any number of other tales of personal invasion and horrific transformation. For example…

Libronomicon: Candace wakes up, ominously, to Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

Madness Takes Its Toll: No madness this week, just mourning.

Ruthanna’s Commentary

Ack. Right. So this is a very good story, and also it turns out that an extended metaphor for cancer complete with the gruesome death of a cat was maybe not actually what I needed to read at this particular moment. I will be going to read some fluffy comfort romance right after I finish writing this post, yes I will.

Anyway, it really is a very good story about inexorable, all-too-predictable horrors, and the sick feeling of seeing them coming on, and the dread of contagion. Zoonotic diseases are bad enough, reminding us in the worst possible way of the kinship between humans and other mammals and the occasional flock of therapods. What does it take for something to be… would that be phytonotic?

*checks* Okay, apparently that is a real word, and I am not pleased. This paper from 1997 hypothesizes the existence of such diseases, and suggests that “Cross-infection transmission experiments, the results of which could add credibility to the hypothesis, could be undertaken.” That’s a very interesting use of the passive voice, now get your abstract out of that Michael Crichton novel and wash it thoroughly. Here’s another from 2014 suggesting that E. coli might be infecting plants as well as riding along on their surfaces, which is admittedly un-dramatic if also unpleasant; they also claim to have made up the word. There are more recent papers about cross-transmissible fungi (of course), and I should probably not take you any further down this rabbit hole—

Anyway, the contagion in “Black Azalea” seems to acknowledge very little distinction between plant, spider, cat, and human. It’s willing to eat everything. And that ticking noise suggests that it’s merely a harbinger. Something worse—something more intelligent and more aware, and perhaps more hungry—is coming behind. I detect in this rapid, grotesque spread a riff on “The Color Out of Space,” which crosses cladistic barriers with similar ease and similar results.

I was also put in mind of Wendy Nikel’s “Leaves of Dust,” where lawn care plays a likewise intense role for a recently-isolated woman. Nikel’s vegetative tendrils grow from the emotional collapse of a relationship rather than a marriage ending in death, but the challenges are in some ways similar.

Signs of contagion are among our more instinctive fears; revulsion to the smell and touch of decay, to the bitter taste of poison, are built into our sensory processing. So, even in horror that’s trying to describe something beyond human experience, authors tend to make scent and texture and taste viscerally recognizable even when other senses fail. Lovecraft’s Color leaves people and plants brittle and crumbling, or sometimes bubbling and oozy—much like this week’s invasion. Mi-go stink. So do abomination-summoning sushi rolls. Sonya Taaffe gives us pleasant (if dangerous) smells; I can’t think of many other attractive or even attractive-repulsive scents in our long list of stories. Wagner comes down squarely on the side of squick and retch, appropriate under the circumstances.

Final thought: how much of the thing in the hole has been blighting the azalea from the start, and how much is summoned by Candace’s fatalistic musings? Normally cosmic horror hangs on a chaotic universe with no real meaning or predictability, but given that Candace’s terror is of destruction “right on schedule”, I wonder if what’s being played with here is the fear—“What could I have done differently?”—that maybe you did have some control. That maybe the wrong thought or action can summon disease, bringing on death as irrevocable and mechanical as a machine.

Not a comfortable thought. I’m gonna go read that romance novel now.

Anne’s Commentary

A lot of people find stories in which animals suffer an anxiety-trigger greater than stories in which only humans suffer, although stories in which the sufferers are young children pose a similar trigger threat. How I parse this is that we may consider animals and children both more vulnerable and more innocent (in a moral sense) than human adults. They can’t have done anything to deserve pain! What they deserve is loving care and protection! Right? Except maybe for those damn raccoons that keep knocking over the garbage cans. Also the objects of your pet zoological phobias, generically. All centipedes must die, I say, at least the ones that dare to enter MY HOUSE. I’m generous. They can burrow in the compost bin, what more can the bastards want?

Ahem.

Wagner’s “Black Azalea” features (horribly-spectacularly) one animal death. I suspected that was coming the moment Enoch was introduced, especially after he got all growly and stiff about the azalea hole. Cats hear things we can’t, as Candace points out. When Enoch darted out of the house and failed all day to respond to Candace’s calls—and his own appetite—I dreaded he was a goner. But equally dread-producing for me was the dissolution of so much flora. If anything’s more innocent than animals and children, it’s plants. Except maybe for those damn garlic chives that rewarded my cultivation efforts by TAKING OVER THE WHOLE DAMN GARDEN. And poison ivy, of course. Poison ivy must die, except when it’s well away from my garden. I’m generous.

As a fellow gardener, I instantly sympathized with Candace. I had a wisteria vine on my back fence that had self-seeded exactly where I would have planted it. Despite knowing the vine would need constant pruning to keep it from overwhelming its bedmates, I loved that wisteria with its intricate purple-and-cream blossoms. On its last spring, it clothed itself in tender-green foliage and flowering racemes more than a foot long. Then, mid-summer, overnight, its leaves began to droop, and wither, and drop, leaving a forlorn skeleton. At last accepting it was gone, I did a post-mortem down to the roots and found no signs of disease beyond, well, death. The huge parent wisteria next door was thriving, and none of the corpse’s bedmates got sick—I would have really dissolved if my magnificent decades-old Zephirine Drouhin rose had started wilting.

Actually, I’d have dissolved if I’d found the stinking black blight Candace did, then seen it jumping species while widening the pit from whence its first victim was wrenched. Ultimate gardener’s nightmare, particularly if the gardener were also acquainted with Lovecraft’s “Color Out of Space.” For aeons, a meteorite might have lain deep under what would become the Moores’ garden. Slow but inexorable, its passengers might have clicked upward, slimifying all they passed, until they reached the roots of Graham’s azalea, and the daisies and grass and dandelions, and Enoch, and Candace. This blight not only jumps species, it jumps whole kingdoms! No wonder Gutierrez finds no mundane disease markers. He may be excited now, but panic is bound to be his team’s response to what they find on the second visit….

Candace first identifies the clicking-ticking with trains, a mechanical noise. I imagine it more like an insect noise, or a crustacean noise, or some amalgamation of the two wholly alien. The associated smell, mildew-fishy, also spans kingdoms of life, maybe as close an identification as human olfaction can manage. Positively uncanny is how Candace wakes to the end of Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1956). The famous line she can’t recall is Dr. Miles Bennell screaming “They’re here already! You’re next! You’re next!”

Intertwining with the weird horrors of “Black Azalea” are the all-too-everyday horrors of human frailty and human loss. Graham succumbs to the swift and nasty depredations of pancreatic cancer, leaving her not only without him but without the stimulating career she gave up to nurse him. Graham may find a metaphorical echo in the old tree killed by Dutch elm disease, Candace in the azalea which declines without the tree’s shelter. As high-powered as she may have been at work, in domestic life she believes the world is “a vicious, ugly place for a woman alone.” Forget the world. Her house is a danger, from the slick tile floor to the step into the sunken living room.

Presumably, Graham installed the tiles and created or preserved the step, thus creating dangers from which only he could rescue Candace. Does she resent him for making her dependent? Is this why she resists her counselor’s suggestion to cherish Graham’s “legacy”? Plus it’s Graham’s illness that deprived her of the independence of a career, although she acknowledges her own zeal to caretake made her give up work irretrievably.

From another angle, it’s Graham who selected the azalea, an incursion into Candace’s domain he rarely made. Maybe the azalea metaphorically represents Graham, whose death poisons Candace’s garden, “her ever-expanding project, her art,” her “child.” There is a subtle uneasiness in the relationship between the spouses, a layer of uneasiness superimposed on the contamination horror.

I mourn the loss of Candace’s garden, which I fear is about to be as plagued as the one in John Langan’s Return-of-the-Old-Ones story, “The Shallows.” Old Ones are Agent Orange to earthly flora, as we’ve often seen in the blasted heaths They create.

Next week, we continue T. Kingfisher’s The Hollow Places with Chapters 11-12, in which it’s time to leave our semi-cozy bunker and do some more exploring.

Ruthanna Emrys is the author of the Innsmouth Legacy series, including Winter Tide and Deep Roots. Her short story collection, Imperfect Commentaries, is available from Lethe Press. You can find some of her fiction, weird and otherwise, on Tor.com, most recently “The Word of Flesh and Soul.” Ruthanna is online on Twitter and Patreon, and offline in a mysterious manor house with her large, chaotic household—mostly mammalian—outside Washington DC.

Anne M. Pillsworth’s short story “The Madonna of the Abattoir” appears on Tor.com. Her young adult Mythos novel, Summoned, is available from Tor Teen along with sequel Fathomless. She lives in Edgewood, a Victorian trolley car suburb of Providence, Rhode Island, uncomfortably near Joseph Curwen’s underground laboratory.